The appellant-Central Bureau of Investigation after registering the First Information Report at 02:00 pm on 16.12.2004 for offences under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 laid a trap in the evening on the same day wherein the respondent is said to have accepted bribe to set the things right for the radiologist conducting PreNatal test to determine the sex of the foetus in contravention of the Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Act, 1994. 2.2.The Special Judge, CBI, rejected the application for discharge vide order dated 30.04.2006 which was carried in revision before the High Court and was registered as Criminal Petition No.366 of 2006. In this case, in view of the discussion above, it is clear that the provisions of Section 6 A(1) of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 are mandatory and not merely directory.

If the approval is not given by the Central Government, then the same shall be notified to the Special Judge who shall then close the case.” 2.3.The CBI, feeling aggrieved by the judgment of the Delhi High Court, has preferred the present appeal substantially on the ground that Section 6A(2) of DSPE Act would be applicable and not Section 6A(1) thereof. In view of our foregoing discussion, we hold that Section 6A(1), which requires approval of the Central Government to conduct any inquiry or investigation into any offence alleged to have been committed under the PC Act, 1988 where such allegation relates to: (a) the employees of the Central Government of the level of Joint Secretary and above, and (b) such officers appointed by the Central Government in corporations established by or under any Central Act, government companies, societies and local authorities owned or controlled by the Government, is invalid and violative of Article 14 of the Constitution. Relying upon the judgments regarding retrospective or prospective applicability of the said declaration, the appellant-CBI would submit that once Section 6A(1) has been declared to be violative of Article 14, the judgment of the High Court deserves to be set aside and the prosecution should be allowed to continue with the proceedings from the stage of rejection of discharge application. The matter was thereafter taken up on 10.03.2016 when this Court, after recording the submissions advanced by the rival parties and considering the importance of the question and also the fact that the retrospectivity or prospectivity of the judgment in the case of Subramanian Swamy (supra) could only be dealt with by a Constitution Bench, directed that the matter be placed before the Chief Justice of India on the administrative side for constituting an appropriate Bench. A prosecution under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 was sought to be questioned by the respondent accused on the basis of the provisions contained in Section 6A(1) of the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, 1946 which was brought in by an amendment in the year 2003.

The provisions of Section 6A(1) of the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, 1946 has been held to be unconstitutional being violative of Article 14 of the Constitution of India by a Constitution Bench of this Court in Subramanian Swamy versus Director, Central Bureau of Investigation and another [(2014) 8 SCC 682]. Though a large number of precedents have been cited at the Bar to persuade us to take either of the above views, as would support the case of the rival parties, we are of the considered view that this question should receive the consideration of a Constitution Bench in view of the provisions of Article 145(3) of the Constitution of India. Prabhakar and others [(2004) 5 SCC 551] one of the questions referred is whether the scope and ambit of Article 20 of the Constitution of India is to be understood to be protecting the substantial rights or the immunity enjoyed by an accused at the time of commission of the offence for which he has been charged.

Whether there can be a deprivation of such immunity by a retrospective operation of a judgment of the Court, in the context of Article 20 of the Constitution of India, is the moot question that arises for determination in the present case. Section 6A of the DSPE Act is a mere procedural provision and not a penal provision as such would not attract Article 20(1) of the Constitution. He enlisted the following aspects in this respect: (a) Article 20 is limited in application wherein distinct offences are created subsequently; (b) The other aspect of Article 20 is debarring infliction of greater penalty, post commission of the offence; (c) Section 6A did not decriminalise PC Act offences and removal of the said provision, therefore, does not create a new offence; (d) Section 6A did not provide any blanket immunity against anti- corruption laws and therefore, removal of the same does not create a new offence; (e) Section 6A did not create any vested right which can be said to be covered by Article 20; (f) Declaration of Section 6A as invalid and unconstitutional is through a judicial order and not a legislative measure. Prior to insertion of Section 6A in the DSPE Act, similar provision was existing in Single Directive No.4.7(3) requiring prior sanction to investigation. Union of India and Another, amongst other larger issues was also testing the validity of the Single Directive No.4.7(3). 10.6.As a result of such declaration Section 6A was introduced in the DSPE Act in the year 2003 vide Section 26(c) of the Central Vigilance Commission Act, 2003 w.e.f. (e) It was not aimed as an immunity or substantive exclusion from application of laws, rather was a preliminary check provided in order to ensure honest officials are not unnecessarily harassed. The State of Uttar Pradesh and Others ; (5) Mahendra Lal Jaini Vs. The State of Uttar Pradesh and Others ; (6) Municipal Committee, Amritsar and others Vs. If the Constitution Bench in the case of Subramanian Swamy (supra) had any intentions of declaring that the same would be prospective in application, then the same should have been specifically and discretely stated therein. State of Karnataka and others for the proposition that if prospective overruling is not specifically provided in the decision, it would not be open for Courts in future to declare such a decision to be prospective in nature. Doe et al ; B: For Union of India: 11.Shri S.V. Raju, learned Additional Solicitor General of India made submissions on behalf of the Union of India. 11.3.Further referring to the definition of the word “investigation” in Section 2(h) of Cr.P.C., it was submitted that the prohibition contained in Section 6A of the DSPE Act relates to the prohibition from collecting evidence in an enquiry or during the investigation. It was submitted that where a Magistrate has already taken cognizance upon an investigation, conducted without the approval under Section 6A of the DSPE Act, the Court can act on evidence collected during such investigation and the proceedings would not be vitiated in the absence of any prejudice both actual and pleaded with respect to such evidence. It was, thus, submitted that after judgment in the case of Subramanian Swamy (supra ), the prohibition contained in Section 6A of the DSPE Act having seized the CBI could investigate the matter subject to Section 17(A) of the PC Act, 1988 wherever applicable. Assuming that Section 6A of the DSPE Act was in operation prior to the judgment in the case of Subramanian Swamy (supra), it could not bar investigation by an Agency other than those covered by the DSPE Act. Initially Union of India was not a party to the proceedings, however, pursuant to an order dated 27.04.2012 passed in this appeal, the Union of India was made a party by the Court suo moto. Even though the FIR was registered only under Section 7 of the PC Act, 1988 against the respondent alone, but still the CBI conducted investigation regarding possessing assets disproportionate to known sources of income not only against the respondent but also his wife, who was working as an employee of the State of U.P. 12.5.An argument relating to discrimination has also been raised by the respondent to the effect that in case if the contention of the appellant is accepted, the respondent would be discriminated from those set of government servants who have availed the protection of Section 6A of the DSPE Act and the proceedings against them have come to a closure in cases where the competent authority declined to grant sanction and also to another set of cases where the Courts have quashed the proceedings in the absence of sanction under Section 6A of the DSPE Act. It was next submitted that appeal of the CBI has been filed primarily on two grounds; that Section 6A(1) of the DSPE Act is not mandatory; and that Section 6A(2) would apply. After referring to the question referred to the Constitution Bench, Shri Datar, learned Senior Advocate submitted that following three questions also arise for consideration namely: (i) Whether declaration of a law being violative of Article 14 or any other Article contained in Part- III is void ab initio under Article 13(2)? Referring to Article 20(1) of the Constitution vis-a-vis deprivation of immunity retrospectively and analysing the said constitutional provision, it is submitted that a conviction of an accused can take place by following the prescribed procedure starting from enquiry, investigation, trial etc. 13.4.Section 6A was declared ultra vires Article 14 of the Constitution and, as such, under Article 13(2) of the Constitution it is void to the extent of the contravention.

The use of the word “void” in the context of the Constitution, unlike the Contract Act, only means that a judicial declaration renders a law inoperative or unenforceable; (e) The Oxford Dictionary defines the word ” void ” in two ways: (i) As an adjective, it means that ‘something is not valid or legally binding’; and (ii) As a verb, it means ‘to declare that (something) is not valid or legally binding’. 13.6.The next submission is that an administrative act, unless declared invalid, will continue to have legal effect and actions taken before the law was declared invalid would still remain protected. It was next submitted that protection from prosecution has continued from 1969 as it was deemed necessary to ensure proper administrative function by Government officials except for brief periods when this Court had struck down the validity of the relevant clause of the Single Directive in the case of Vineet Narain (supra) and, thereafter, Section 6A of the DSPE Act in the case of Subramanian Swamy (supra).

(iii) The declaration of Section 6A of the DSPE Act as unconstitutional and violative of Article 14 of the Constitution would have a retrospective effect or would apply prospectively from the date of its declaration as unconstitutional? Directive No.4.7(3) contained instructions regarding modalities of initiating an enquiry or registering a case against certain categories of civil servants and provided for a prior sanction of the Designated Authority to initiate investigation against officers of the Government and public sector undertakings & Nationalized Banks above a certain level. The same reads as follows: “4.7(3)(i) In regard to any person who is or has been a decision making level officer (Joint Secretary or equivalent of above in the Central government or such officers as are or have been on deputation to a Public Sector Undertaking; officers of the Reserve Bank of India of the level equivalent to Joint Secretary of above in the Central Government, Executive Directors and above SEBI and Chairman & Managing Director and Executive Directors and such of the Bank officers who are one level below the Board of Nationalised Banks), there should be prior sanction of the Secretary of the Ministry/Department concerned before SPE takes up any enquiry (PE or RC), including ordering search in respect of them. In respect of the officers of the rank of Secretary or Principal Secretary to Government, such references should be made by the Director, CBI to the Cabinet Secretary for consideration of a Committee consisting of the Cabinet Secretary as its Chairman and the Law Secretary and the Secretary (Personnel) as its members. Thereafter, in 2003, Section 6A, akin to Single Directive No.4.7(3), was inserted in the DSPE Act w.e.f. ( 2) Notwithstanding anything contained in sub-section (1), no such approval shall be necessary for cases involving arrest of a person on the spot on the charge of accepting or attempting to accept any gratification other than legal remuneration referred to in clause (c) of the Explanation to section 7 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (49 of 1988). Enquiry or Inquiry or investigation of offences relatable to recommendations made or decision taken by public servant in discharge of official functions or duties.– No police officer shall conduct any enquiry or inquiry or investigation into any offence alleged to have been committed by a public servant under this Act, where the alleged offence is relatable to any recommendation made or decision taken by such public servant in discharge of his official functions or duties, without the previous approval– (a) in the case of a person who is or was employed, at the time when the offence was alleged to have been committed, in connection with the affairs of the Union, of that Government; (b) in the case of a person who is or was employed, at the time when the offence was alleged to have been committed, in connection with the affairs of a State, of that Government; (c) in the case of any other person, of the authority competent to remove him from his office, at the time when the offence was alleged to have been committed: Provided that no such approval shall be necessary for cases involving arrest of a person on the spot on the charge of accepting or attempting to accept any undue advantage for himself or for any other person: Provided further that the concerned authority shall Article 20(1) of the Constitution and its applicability in the context of Section 6A of the DSPE Act (Question No. Sub-Section (2) begins with a non- obstante clause stating that no such approval would be necessary for cases involving arrest of a person on the spot on the charge of accepting or attempting to accept any gratification other than legal remuneration referred to in clause (c) of the Explanation to Section 7 of the PC Act, 1988.

23.Before proceeding to do that, it would be appropriate to examine whether Section 6A of the DSPE Act providing protection to certain categories of Government servants would, in any manner, amount to a conviction or sentence or it would be a purely procedural aspect. Datar to canvass that Section 6A of the DSPE Act is not part of procedural law and that it in any manner introduces any conviction or enhances any sentence post the commission of offence. Trial under a procedure different from the one when at the time of commission of an offence, or by a court different from the time when the offence was committed is not unconstitutional on account of violation of sub-article (1) to Article 20 of the Constitution.

28.The right under first part of sub-article (1) to Article 20 of the Constitution is a very valuable right, which must be safeguarded and protected by the courts as it is a constitutional mandate. Interpreting the term ‘law in force’, it was held that the ordinance giving retrospective effect would not fall within the meaning of the phrase ‘law in force’ as used in sub-article (1) of Article 20 of the Constitution. 30.The aforesaid rationale and principles of interpretation equally apply to the second part of sub-article (1) to Article 20, which states that a person can only be subjected to penalties prescribed under the law at the time when the offence for which he is charged was committed. It would be appropriate to reproduce the said provision hereunder: “Where this Act, or any Central Act or Regulation made after the commencement of this Act, repeals any enactment hitherto made or hereafter to be made, then, unless a different intention appears, the repeal shall not- (a) revive anything not in force or existing at the time at which the repeal takes effect; or (b) affect the previous operation of any enactment so repealed or anything duly done or suffered thereunder; or (c) affect any right, privilege, obligation or liability acquired, accrued or incurred under any enactment so repealed; or (d) affect any penalty, forfeiture or punishment incurred in respect of any offence committed against any enactment so repealed; or (e) affect any investigation, legal proceeding or remedy in respect of any such right, privilege, obligation, liability, penalty, forfeiture or punishment as aforesaid; and any such investigation, legal proceeding or remedy may be instituted, continued or enforced, and any such penalty, forfeiture or punishment may be imposed as if the repealing Act or Regulation had not been passed.” A plain reading of the above provision indicates that the repeal of an enactment shall not affect previous operation, unless a different intention appears. The other issue raised with regard to Article 20(1) of the Constitution was that although the offence had been committed in the month of March and April 1949 but by way of an ordinance which came into force in September 1949, the laws were adopted which covered the offences for which the appellants were charged and as such Article 20(1) would protect them and they could not be tried for such offence which had been introduced later on. Such trial under a procedure different from what obtained at the time of the commission of the offence or by a court different from that which had competence at the time cannot ipso facto be held to be unconstitutional.

set aside the forfeiture on the ground that the 1944 Ordinance had come into force on 23.08.1944 whereas the effective period for committing the offence had ended in July 1944. (vi)The Constitution Bench once again relied upon the earlier Constitution bench judgment in the case of Rao Shiv Bahadur Singh (supra) and laid down that forfeiture in the said case would have nothing to do with conviction or punishment and therefore there could be no application of Article 20(1). Therefore, this case shows that it is only conviction and punishment as defined in Section 53 of the Indian Penal Code which are included within Article 20(1) and a conviction under an ex post facto law or a punishment under an ex post facto law would be hit by Article 20(1); but the provisions of Section 13(3) with which we are concerned in the present appeal have nothing to do with conviction or punishment and therefore Article 20(1) in our opinion can have no application to the orders passed under Section 13(3). (viii) The Constitution Bench in the case of Sukumar Pyne (supra), relying upon the earlier Constitution Bench in Rao Shiv Bahadur Singh (supra), further laid down that there is no principle underlying Article 20(1) of the Constitution which makes a right to any course of procedure a vested right. Nayyar (supra), a two-judge Bench of this Court, while dealing with the effect of repeal and revival of Section 5(3) of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1947, was of the view that Section 5(3) did not by itself lay down or introduce any offence.

It was contended that by shifting the burden of proof as provided for in Section 5(3) of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1947, a new offence is created. Subsequently, Section 304-B of the IPC was introduced in the Indian Penal Code through Amending Act No 43 of 1986, which came into effect on November 19, 1986. It was of the view that for any law which affects matters of procedure, the same would apply to all actions, pending as well as future and no procedural amendment could be said to be creating an offence; and, accordingly, disagreed with the view of the Appellate Tribunal, and upheld the order passed by the Chairman, SEBI that retrospective insertion of Section 11B of the SEBI Act cannot be hit by Article 20(1) of the Constitution. Datar, learned counsel has sought to canvass that the marginal note along with Article 20 of the Constitution refers to protection in respect of conviction and, therefore, anything which may relate to or may be a pre-requisite for conviction should stand covered by Article 20(1) of the Constitution. 37.The Constitution Bench in case of Subramanian Swamy (supra) declared Section 6A of the DSPE Act as unconstitutional on the ground that it violates Article 14 of the Constitution on account of the classification of the Government servants, to which the said provision was to apply. 39.Much emphasis has been laid on the interpretation of the word ‘ void’ used in Article 13(2) of the Constitution. The State shall not make any law which takes away or abridges the rights conferred by this Part and any law made in contravention of this clause shall, to the extent of the contravention, be void.” 41.Under Article 13(1) all existing laws prior to the commencement of the Constitution, insofar as they are inconsistent with the provisions of Part-III, would be void to the extent of inconsistency. However, reliance is placed upon the judgments on Article 13(1) while interpreting the word ‘ void ’ used in Article 13(2). The appellant therein took an objection that provisions of 1931 Act were ultra vires of Article 19(1)(a) read with Article 13(1) of the Constitution and would, therefore, be void and inoperative as such he may be acquitted. As already explained, Article 13 (1) only has the effect of nullifying or rendering all inconsistent existing laws ineffectual or nugatory and devoid of any legal force or binding effect only with respect to the exercise of fundamental rights on and after the date of the commencement of the Constitution. So far as the past acts are concerned the law exists, notwithstanding that it does not exist with respect to the future exercise of fundamental rights.” However, Justice Fazal Ali was of the view that though there can be no doubt that Article 13(1) will have no retrospective operation and transactions which are past and closed, and rights which have already vested will remain untouched. But with regard to inchoate matters which were still not determined when the Constitution came into force, and as regards proceedings whether not yet begun, or pending at the time of the enforcement of the Constitution and not yet prosecuted to a final judgment, the very serious question arises as to whether a law which has been declared by the Constitution to be completely ineffectual can yet be applied.” (iii)In the case of Behram Khurshed Pesikaka (supra), a seven-judge Bench of this Court was considering the legal effect of the declaration made in the case of State of Bombay Vs. In paragraph 41, while dealing with difference between law being unconstitutional on account of it being not within the competence of the legislature or because it was offending some constitutional restrictions differentiated between the two.

Thus, a legislation on a topic not within the competence of the legislature and a legislation within its competence but violative of constitutional limitations have both the same reckoning in a court of law; they are both of them unenforceable. (emphasis supplied)” The distinction drawn was that where a law is not within the domain of the legislature, it is absolutely null and void. Article 13(1) deals with laws in force in the territory of India before the commencement of the Constitution and such laws in so far as they are inconsistent with the provisions of Part III shall, to the extent of such inconsistency be void. (2) of that article imposes a prohibition on the State making laws taking away or abridging the rights conferred by Part III and declares that laws made in contravention of this clause shall, to the extent of the contravention, be void. A plain reading of the clause indicates, without any reasonable doubt, that the prohibition goes to the root of the matter and limits the State’ s power to make law; the law made in spite of the prohibition is a still- born law. 24 of the report, the Bench proceeds to deal with the effect of an amendment in the Constitution, with respect to the pre-Constitutional laws, holding that removing the inconsistency would result in revival of such laws by virtue of doctrine of eclipse as the pre-existing laws were not still born. 13 (1) was considered in Keshava Madhava Menon’ s caseand again in Behram Khurshed Pesikaka’ s caseIn the later case, Mahajan, C. J., pointed out thatthe majority in Keshava Madhava Menon’ s case (3) clearly held that the word “void” in Art. 13(1) with respect to existing laws insofar as they were unconstitutional was only that it nullified them, and made them “‘ ineffectual and nugatory and devoid of any legal force or binding effect”. 13(2), namely, that the laws which were void were ineffectual and nugatory and devoid of any legal force or binding effect. This distinction between the voidness in one case and the voidness in the other arises from the circumstance that one is a pre- Constitution law and the other is a post- Constitution law; but the meaning of the word void” is the same in either case, namely, that the law is ineffectual and nugatory and devoid of any legal force or binding effect.

13 (2) arising from the fact that one is dealing with pre-Constitution laws, and the other is dealing with post- Constitution laws, with the result that in one case the laws being not still-born the doctrine of eclipse will apply while in the other case the laws being still born-there will be no scope for the application of the doctrine of eclipse. However, in the case of the second clause, applicable to post Constitution laws, the Constitution does not recognise their existence, having been made in defiance of a prohibition to make them. In the case of post- Constitution laws, it would be hardly appropriate to distinguish between laws which are wholly void-as for instance, those which contravene Art. Nageswara Rao, speaking for the Bench, observed that where a statute is adjudged to be unconstitutional, it is as if it had never been and any law held to be unconstitutional for whatever reason, whether due to lack of legislative competence or in violation of fundamental rights, would be void ab initio. An unconstitutional law, be it either due to lack of legislative competence or in violation of fundamental rights guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution of India, is void” ab initio.

summarised the following propositions: “(a) Whether the Constitution affirmatively confers power on the legislature to make laws subject-wise or negatively prohibits it from infringing any fundamental right, they represent only two aspects of want of legislative power; (b) The Constitution in express terms makes the power of a legislature to make laws in regard to the entries in the Lists of the Seventh Schedule subject to the other provisions of the Constitution and thereby circumscribes or reduces the said power by the limitations laid down in Part III of the Constitution; (c) It follows from the premises that a law made in derogation or in excess of that power would be ab initio void… 28 to state that a statute declared unconstitutional by a court of law would be still born and non est for all purposes.

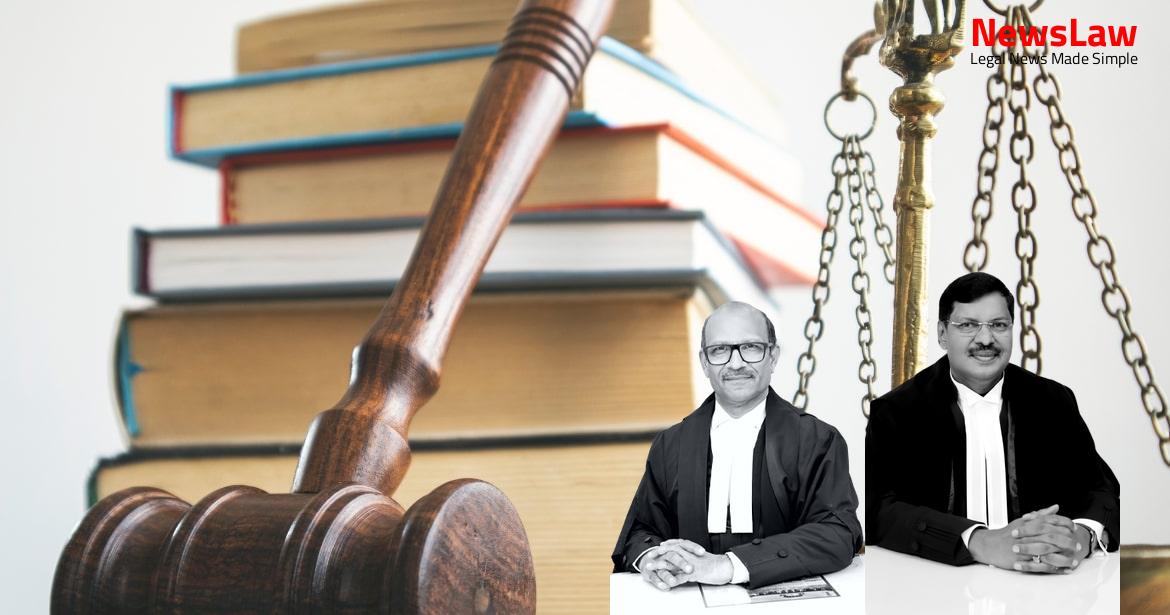

Case Title: CBI Vs. R.R. KISHORE

Case Number: CRIMINAL APPEAL NO.377 OF 2007 (2023INSC817)